This week I performed “Sonora Rivers,” with music by composer Yuanyuan (Kay) He and text by me, at six Tucson Symphony Orchestra Young People’s Concerts, one concert under stars in Reid Park with the Tucson Pops Orchestra, and one at Ironwood Ridge High School. And that’s not the total of the Watershed Soundscape project’s concerts, only the ones I could fit in my schedule. I’m grateful to the narrators who filled in at over twenty high schools and other venues—and to all the high school music directors and students who learned and performed the piece.

The TSO concerts, held at Linda Ronstadt Music Hall, were very special. Over 12,000 students grades 3 - 6+ came from more than 80 schools in southern Arizona and were somehow wrangled in orderly fashion into the concert hall for the six programs that included a bit of the William Tell Overture, Appalachian Spring, the Grand Canyon Suite, Mozart’s 41st Symphony, John Williams’s score for Jurassic Park, and a piece by Katy Dilley, a participant in TSO’s Young Composer’s Project.

I served as narrator for the whole concert in the role of Ranger Park the park ranger, partnering with TSO’s Ben Nesbit on a script that took students on a tour of the orchestra and of our watershed. What a thrill. And what a model of community engagement for University of Arizona and the TSO. The students too did their part, eagerly following Ranger Park’s directions for creating a monsoon rainfall in the concert hall with the orchestrated percussion of their hands and feet—with a little help from the TSO percussion section’s rainstick, wind machine, and thunder sheet. My gratitude to all involved and especially to Maestro Jose Luis Gomez, whose conducting soulfully guided me through Kay’s “Sonoran Rivers”—that is, after I ditched the ranger hat.

Ranger Park the Park Ranger

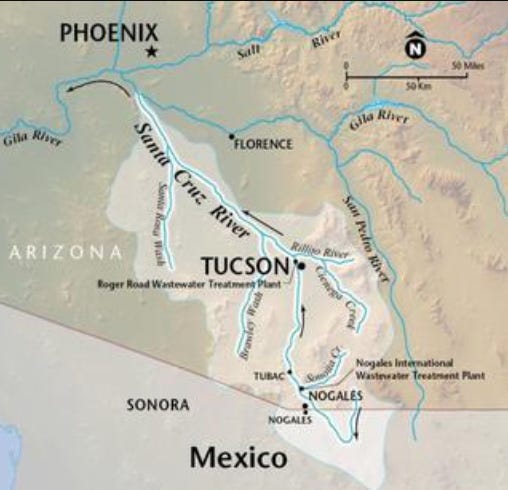

Santa Cruz River Watershed

Watershed Soundscape team: Jackie Glazier, Yuanyuan (Kay) He, Alison Deming, Sara Fraker.

When Sara Fraker, UA Associate Professor of Oboe, invited me to join the Watershed Soundscape team, I don’t think either one of knew what we were getting into. We wanted to learn about issues critical to the living waters of our Santa Cruz watershed and to promote education and exploration that encourage water conservation and habitat restoration in a region beleaguered by a prolonged drought and the pressures of development, mining, and agriculture. We had many collaborators in that learning. How would music and text interact? How would science and art and cultural perspective interact? How would flow data from the river be transformed into music? We entered into this with good intentions and faith in the artistic process and what a joy it has turned out to be. Jackie Glazier, Associate Professor in the College of Music, clarinetist and advocate of new music, handled with characteristic good cheer the coordination of all the high school concerts.

Details about the project, our collaborators, and our sponsor, UA’s Arizona Institute for Resilience, are here. In time, I hope to post an audio recording.

Here is the text that accompanies Yuanyuan (Kay) He’s “Sonoran Rivers.”

SONORAN RIVERS: A Celebration of Desert Water

Text by Alison Hawthorne Deming

THE DESERT

The Santa Cruz River is a desert dweller. A desert traveler.

Gathering drop by drop, seep by seep, runnel by runnel, water drains out of mountains, and collects into a streambed. Streambed by streambed, water merges into a creek, creek by creek, water becomes a river. Water reshapes itself, traveling through the land, snaking its way forward, shaping the terrain. Water sings as it travels—riffle, babble, gurgle, swoosh. Its music gentles the air, until monsoon rain makes it roar, ripping out brush, snapping trees, sending them crashing downstream. Then the river stills to an almost imperceptible hum. And then it vanishes.

LAS CIENEGAS (THE MARSHES)

The road from Tucson to Sonoita leaves city sprawl and desert scrub behind, climbs into rolling hills of oak and piñon, then slopes down to sweeping golden grasslands dotted with mesquites. A seam of bright green cottonwoods marks a course of living water, the lush riparian corridor of Cienega Creek.

Water in the desert is an invitation to life. A community of creatures visits the flowing creek. Coyote, bobcat, pronghorn antelope, coatimundi, and one hundred species of migrating birds. Endangered wetland species inhabit the waters: Gila topminnow, Gila chub, and the snoring Chiricahua leopard frog.

THE PEOPLE

For at least 12,000 years Indigenous people have lived and hunted along the Santa Cruz River. Between 200 BCE and 1450 AD the Hohokam settled there in villages. Skilled water engineers, they built canals, channeling water from the river to their crops. They built terraces and rock dams to capture rainwater. The Hohokam communally grew tepary beans, yellow melon, squash, and corn. Their knowledge of the desert made them agile at dryland farming. The O’odham people believe these were their ancestors.

The O’odham’s traditional knowledge of the land and water reaches deep in time. Their calendar reflects this learned relationship with place. May is Mesquite Bean Harvest Moon. June: Saguaro Fruit Ripening Moon. July: Big Rains Moon. August: Short Planting Moon. September: Dry Grass Moon.

The Wa:k Community at San Xavier has restored a section of the river as a shady refuge, the Hikdan, where land and water are held sacred. Water means resilience of the land for the O’odham. Resilience of the land and growing traditional crops means resilience of the culture.

THE CITY

One hundred years ago the river flowed year-round. But agriculture, mining, and development have taken their toll. The water table dropped from 25 feet below the surface to 300 feet, deeper than the roots of cottonwoods or mesquites can reach.

The city of Tucson grew up on the banks of the Santa Cruz River. Here, roughly one million people use 100 million gallons of water each day. Today the river’s path through the city is mostly a bone-dry track of sand with patches of scrub. When the monsoons hit, the river roars for a few days, washing whatever is in its path downstream—sediment, brush, shopping carts, big gulp cups, lost sneakers.

At Tanque Verde Creek, where people have made efforts to restore the land, the aquifer has been steadily recovering and seasonal flows have returned. On spring days, the creek runs crystal clear and willows lean out over the flow. A blizzard of fluffy cottonwood seeds drifts on the breeze. Birdsong trinkles down with the dappled sunlight under cottonwood leaves.

But mostly the urban rivers look like the afterthought of rivers.

THE MUSIC OF THE FUTURE

The music of the future is a music of uncertainty.

What work will we do to protect what we love? We have good tools and rich traditions to draw upon, the technologies for water conservation and habitat restoration. There is so much good work to be done.

Some say frogs were the first singers on Earth. Some say it was water that gave the Earth the gift of melody.

What will be the music of the future?